Spend enough time outdoors, and you’re sure to encounter that dastardly villain commonly known as poison ivy rash. If it hasn’t affected you, it’s left its mark on your friends or your family, and you’re familiar with its itchy tales of woe.

If the ivy isn’t a concern, you’ll run into poison oak or poison sumac sooner or later, so now’s the time to learn more about it. If you’re like me and these irritating plants don’t bother you, learning how to identify and treat the rash is a valuable skill to have. Trust me, you take care of somebody’s PI rash and you’ve made a friend for life!

Table of Contents

Identifying Poison Oak, Sumac, and Ivy

These three plants are relatively easy to identify, so if you keep your eyes open and brush up on a little botanical know-how, you’ll have an advantage over those who prefer blundering through the undergrowth.

As a bit of general knowledge, many plants can really mess up your day. Avoid touching anything you haven’t positively identified, and definitely avoid eating anything you find outdoors without proper training.

Poison Ivy

Poison ivy is botanically known as Toxicodendron radicans and is more closely related to the pistachio than true ivy. You’ll find T. radicans growing all over the United States except in Alaska, California, and Hawaii. It typically prefers soil that’s been worked by humans at some point, so you’ll often find this sucker growing in gardens, parks, and the borders of old farmland.

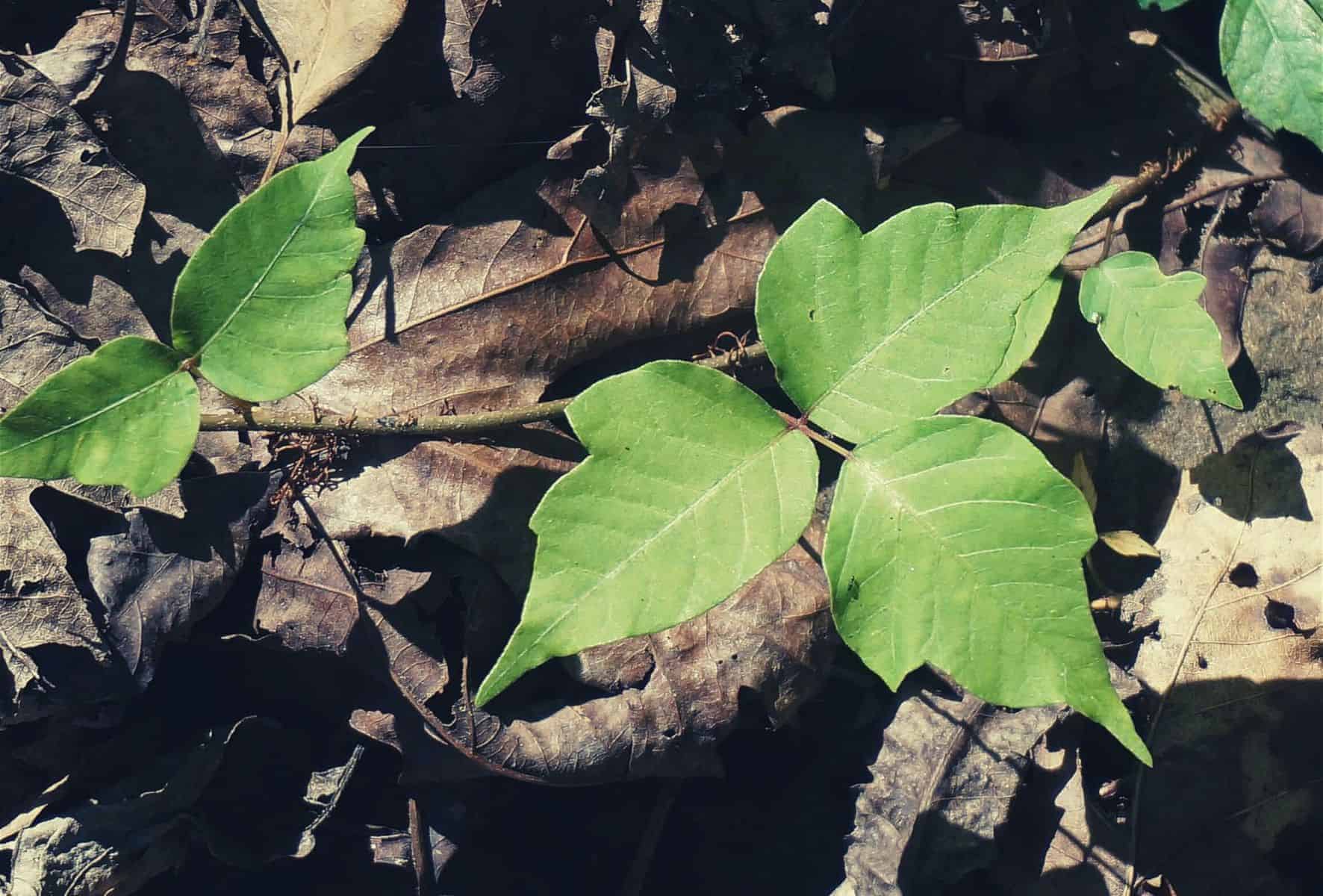

T. radicans is identified by a few regular characteristics, although variations are possible between geographical areas. The leaves will grow in groups of three and tend to be almond or tear-shaped, and each group of leaves is individually attached by a stem to the parent vine. The vine itself tends to be “hairy”. Sometimes the plant has white berries.

Remember these words of wisdom: “leaves of three let it be” and “hairy vine, no friend of mine” to have an easier time identifying this plant in the wild. The leaves are usually emerald green, but in the spring they take on a surprisingly attractive reddish hue.

It can grow as a vine or a short shrub reaching about four feet high. ALL parts of this plant are toxic to people and will cause a poison ivy rash!

Although it causes a rash in humans, many species of wildlife rely on poison ivy as a food source and are not affected by it.

Poison Oak

Toxicodendron diversilobum isn’t as widespread as poison ivy, but it is just as troublesome. You’ll find poison oak in the western United States and the southeastern United States growing in areas of filtered sunlight. It generally will not grow above elevations of 5,000 feet.

Like poison ivy, you can identify poison oak by its groups of three leaves; however, the leaves of poison oak are scalloped and similar to that of oak trees (where this plant gets its common name). Unfortunately poison oak is variable in its leaf appearance.

The only sure-fire identifiers for poison oak are that it has three leaves attached to individual stems and that its leaf stems grow in an alternating fashion. It can grow to be more than one hundred feet long.

Poison Sumac

Toxicodendron vernix is a dweller in wet, swampy areas in the eastern regions of the United States. You probably won’t find much poison sumac because it’s relatively uncommon and prefers saturated areas in standing water or muddy, swampy banks.

The leaves of poison sumac are smooth and grow pinnately; each leaf will have 7-13 leaflets growing opposite of each other. As a full-grown tree, the poison sumac can reach 30 feet in height. Red stems branch off the main trunk and serve as an identifying feature of this toxic plant.

Many people confuse the nasty poison sumac with the beneficial staghorn sumac; poison sumac has leaves that are smooth, while the staghorn has leaves with toothed margins. Poison sumac also grows in the wettest conditions possible, so if you avoid swamps and the thick undergrowth along the edges of ponds you should miss contact with poison sumac.

However, of the three Toxicodendron species we’re talking about, T. vernix is by far the most toxic.

Why Should You Avoid These Poisonous Plants?

These members of the Toxicodendron family all contain an oily, organic compound called “urushiol”. It causes contact dermatitis characterized by a painful and itching reaction in about 85% of people. The oil itself is invisible to the naked eye but has the consistency and persistence of axle grease.

Reactions may not present themselves until days after exposure but usually, consist of raised red bumps that are extremely itchy and swell into blisters. Minor cases result in a few itchy, red lesions that swell and drive the bearer crazy for about a week. More serious reactions could require emergency room visits.

At the basest level you want to avoid a poison ivy rash because it’s itchy and extremely uncomfortable, but advanced cases can be far more serious and require hospitalization.

How to Avoid & Prevent Exposure

The best way to avoid exposure resulting in poison ivy rash is to learn how to identify the culprit and avoid it at all costs.

My favorite go-to guide for all things natural is called “Forest and Thicket”. It’s one of those rare field guides that steps beyond identification and infuses a bit of soul and readability into its words. In this book author John Eastman describes his preferred method of avoiding poison ivy rash,

…when in poison ivy’s vicinity, I conciliate it…by addressing it as ‘my friend.’ – John Eastman

That might look like hippie mumbo-jumbo, and it may very well be, but I find some truth and wisdom in that phrase.

For poison oak, ivy, or sumac to be your friend, you should recognize them at a glance. And if the Toxicodendron family is your friend you’ll treat it with respect; don’t tromp carelessly through the undergrowth.

That works well for me. I have to dispose of hundreds of feet of poison ivy every year in people’s gardens, and I have had great success in carefully, diligently, and respectfully removing the plant from gardens. My coworkers who rip it apart carelessly are the ones who suffer from a rash.

If you’re the pragmatic type and have no desire to make friends with plants, you’ll want to wear long sleeves and long pants everywhere you go outside. Learn to identify the plant and consider what to wear on a hike. If you think you may encounter poison ivy, then wear protective clothing that minimizes or eliminates any contact you could have with the plant.

A hidden cause of PI rash is smoke inhalation. Never, ever burn plant material you’re unfamiliar with. When any member of the Toxicodendron family is burned the smoke releases the urushiol oil that, when inhaled, can be deadly.

How to Treat a Rash

Treating poison ivy is a relatively simple procedure even if it hurts and itches like nothing else while handling it.

Initial Care

- Wash the affected area with soapy, lukewarm water within 8 hours of exposure, preferably with a medicated wash designed to counteract urushiol exposure

- Friction is the most important element for removing urushiol from your skin. Use a washcloth and scrub the exposed areas of your skin vigorously

- Wash all of your clothing that may have been exposed as soon as you can along with the washcloth you used to remove the oil

Longer Term Options

Uh-oh, the itch is setting in… what do you do?!

- DO NOT SCRATCH IT! This can cause infection and slow healing

- Use a product like calamine lotion to soothe those itches

- Cool showers and colloidal baths work wonders in relieving the itch of a rash

- A cold compress can help to alleviate the itch of rashes. When at home a bag of frozen vegetables works wonders, but in the field, an instant cold compress should be included in your camping first aid kit checklist

Key Points

- Don’t wash the rash with hot water. This will open up pores in your skin and make the reaction much more severe

- Try as hard as you can not to scratch or itch the rash, especially when it blisters. This not only slows recovery time but can cause infection

- And on the note of blisters and rashes, poison ivy does not spread from one blister to another. If a rash seems to grow, it’s because of a delayed reaction to initial contact, not because the rash spreads or is contagious (it’s not!)

I work as a gardener and am exposed to poison ivy on a daily basis during the summer. I find no trouble with the stuff because I treat it with respect and make efforts to avoid exposing myself to it blindly, but accidents happen. And many of my more careless coworkers are exposed to poison ivy rash far more regularly than I am.

We go through several bottles of Tecnu a season for one reason; that stuff works wonders with a rash. As long as it’s applied as a wash within 8 hours of exposure, the Tecnu seems to counteract the worst effects.

It’s an inexpensive solution to a terribly irritating problem, so consider adding a container or two to your backpack and first aid kits.

Wrapping Up

Dealing with a poison ivy rash is a pain, and sometimes it’s literally a pain in the butt. The best way to handle this itchy problem is to avoid contracting it in the first place by learning to identify and avoid the plants that cause it. And if you find yourself suffering those itchy red bumps and blisters, you now know how to handle it effectively.